Jay Chen, CFA, PhD

Elnora H. and William B. Quarton Professor of Business Administration and Economics, Coe College, IowaThe Yen's Long Decline, 4/23/2022

The Japanese yen is at a multi-year low against the major currencies. Although my PhD thesis is on the yen carry trade, I haven’t looked at the currency market for years. The development in the yen now is getting lots of attention on my Twitter feed. So I took a look. It is indeed very alarming. A storm is brewing and I plan to bet against the Japanese stocks, especially those bank ADRs. I will use a few posts to tell you the idea I have.

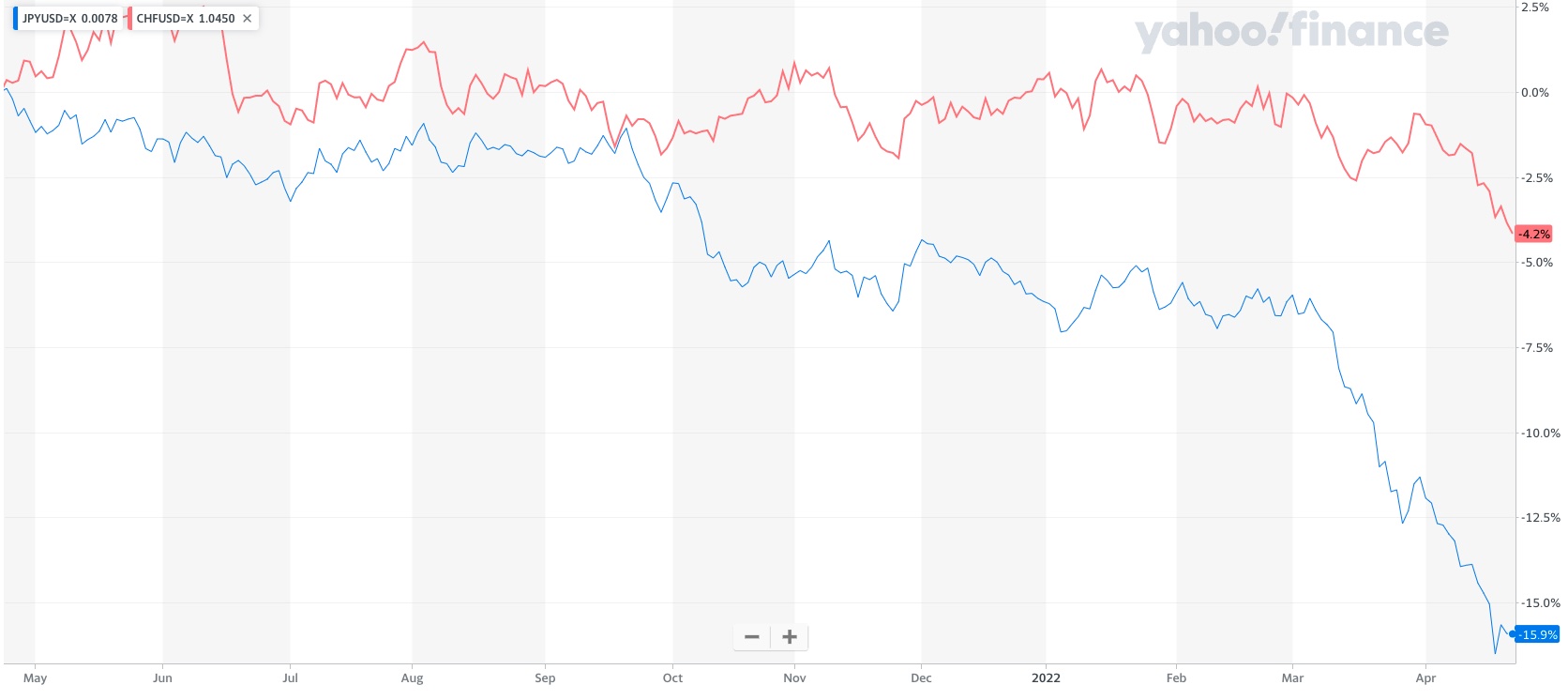

The chart from Yahoo! is clear that the yen is rapidly depreciating vis-a-vis the dollar. The trend can’t be missed and the acceleration of collapse is worrying.

What is really alarming is that the yen used to be a safe haven. When the world is in turmoil, investors fly to safety: the dollar, the yen, and the Swiss franc. But the 2022 turmoil makes the latter two not as attractive as the dollar. We can say that Switzerland is so close to Ukraine that its loss of currency value is understandable. But Japan is far away from the war and its currency depreciation is much larger than the Swiss franc.

The Japanese Finance Minister is in talks with the Treasury Secretary about a joint intervention, but Yellen is unlikely to make the dollar weaker in the face of rising price levels. Japan, of course, can unilaterally intervene in the foreign exchange market and stop the outflow of the yen. After all, Japan still has plenty of foreign reserves to keep the yen from depreciating.

But this outflow might be a change of the structure of the Japanese economy. The Bank of Japan or the Finance Ministry can throw sand in the gears, but can’t stop the turning of the demographic machine.

So the question is why. To put it simply, the government debts finally exceed the threshold that investors believe will not cause the interest rates to rise. Normally, a person, an organization, or a country faces the reality that the more money you borrow, the higher borrowing cost (in terms of higher interest rates) you will have. Japan has defied this fundamental principle for years. No longer. But why now? Covid might play a huge role. I will come back to this point in the next post, but let me tell you that when interest rates start to rise, the behemoth banks in Japan will be hit the hardest. Their balance sheets can’t sustain major rate hikes.

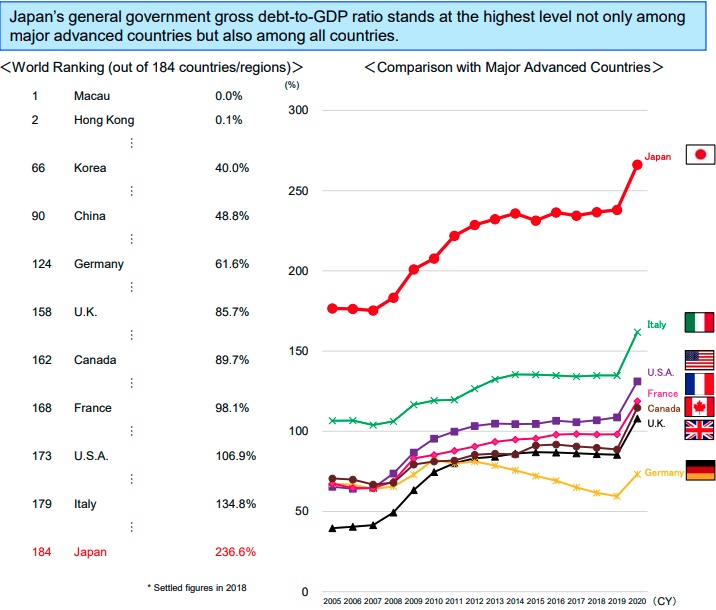

Japan’s debt problem is well known. Look at the chart below. The Ministry of Finance tells you that “Japan’s general government gross debt-to-GDP ratio stands at the highest level not only among major advanced countries but also among all countries.”

We’ve got to appreciate their honesty. If all Japanese people alive spend nothing, eat nothing, and do nothing but make money, they need more than two years to pay off the government debt. There is no way Japan can pay off that kind of national debt.

But it wasn’t a problem before. Why should it be a problem now?

The uptick during the pandemic is part of the reason. When Wile E. Coyote chases the road runner, he can continue to run midair for a while. But once he realizes there's no ground below, he falls. The Japanese government, just like all governments around the world, spent a good deal of money to help the economy and fight the pandemic. It seems to be the prompt Wile E. Coyote needs to realize where he is.

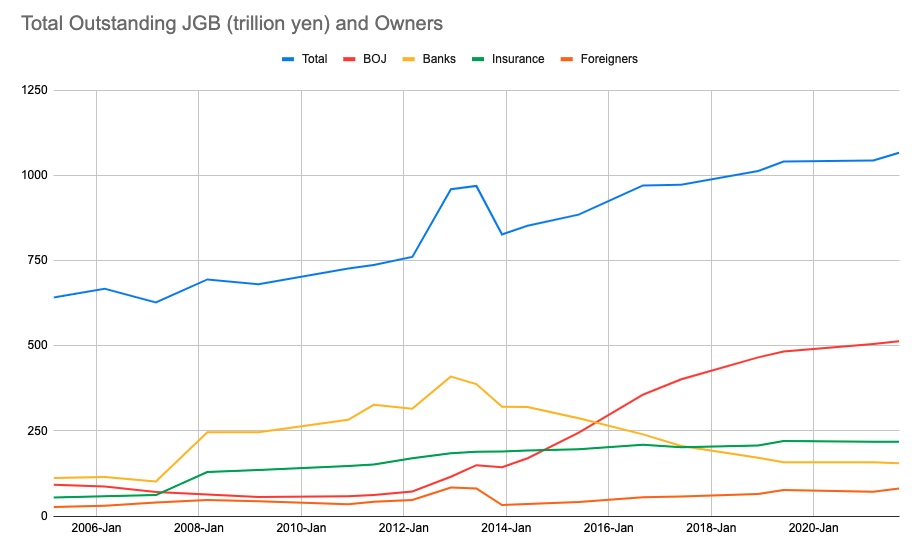

But the shift has been slowly happening, since even before the pandemic. Look at the following chart regarding Japanese Government Bonds’ ownership.

JGBs are just like Treasuries. Japan has no problem borrowing in their own currency. The Japanese people used to be glad to lend their hard-earned savings to the government. Before 2013, banks, which were the conduit savers used to invest in JGBs, were the largest holders of JGBs. But the Bank of Japan, taking a page from the Fed, started to monetize Japan’s government debts, by going on a large scale of quantitative easing. BOJ gradually became the largest holder of JGBs. Insurance companies, the mainstay of JGB holders, keep a relatively stable JGB portion. Their liabilities must be matched with riskless assets. But BOJ absorbs not only the increase in outstanding JGBs, but also banks’ cut in JGB holdings.

Without BOJ’s purchases, JGBs should see a huge spike of the yield (yields move to the opposite direction of bond prices). But Japan can’t afford a high interest rate environment. Like I said in the previous post, Japanese banks will fall like flies if rates are increasing too fast. So BOJ’s job is to keep the interest rates low.

Mitsubishi UFJ Group, one of the largest financial institutions in the world, has a spread between lending rate and deposit rate of 0.75%. JP Morgan Chase’s spread is at least 3%. Just look at the difference and you see why rising interest rates in Japan can be a problem for Japanese banks. Loans are already given out. Banks can’t adjust lending rates overnight, but depositors demand higher interest rates right away. Too much change in the interest rate will create banks’ insolvency problem. Japanese banks also tend to have a bigger part of their business in conventional lending. They don’t have meaningful positions outside of conventional lending to buffer shocks. Japan’s economic activities basically center around these banks.

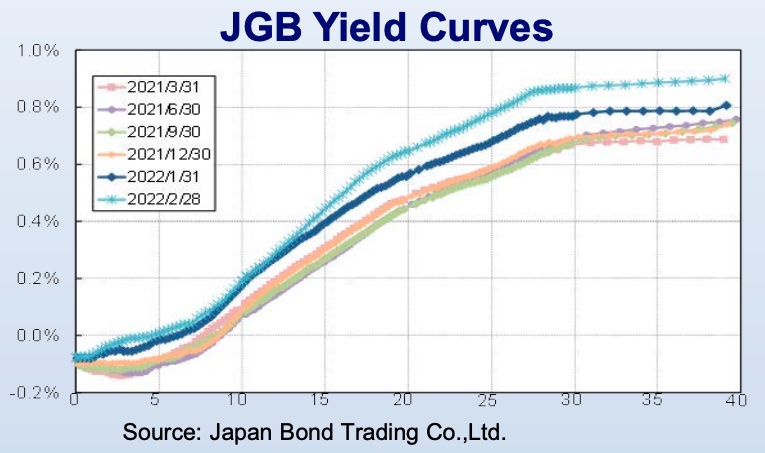

This is the reason why the BOJ can’t allow the rates to hike up as much and as aggressively as the Fed. But the JGB yields are still creeping up. See the yield curves below.

The tension for the BOJ now is how to keep the JGB rate from increasing when the market is showing their distaste for JGBs. The only solution is to print more money to buy more JGBs. But something has to give. There’s no such thing as free lunch. For one, the market will dislike JGBS even more. Eventually the BOJ will become the only buyer of JGBs. More importantly, the real economy will take a hit. When the Japanese economy makes a similar amount of products and services, but the money base explodes, the value of its currency must drop. We should see either inflation or depreciation of the yen. Japan, as opposed to the U.S. and Europe, goes on a different path: it depreciates its currency more than raising the price level.

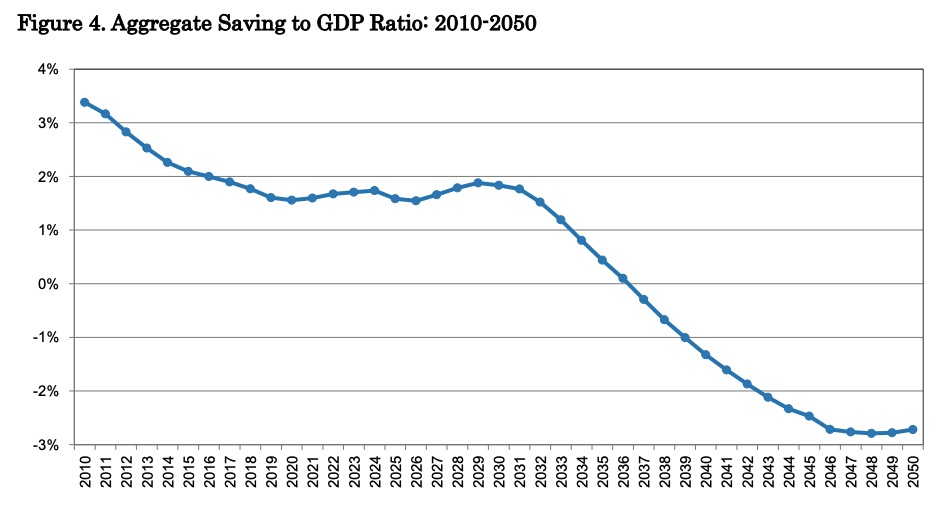

Behind the depreciation is the gradual distrust of the government and the unstoppable demographic force. The exodus of domestic and foreign money will finally meet Japan’s demographic implosion. At this moment, Japan is still a country that saves (more export than import), but retired people can’t save. Takeo Hoshi, a noted professor at the University of Tokyo, wrote a paper in 2013 (Defying Gravity: Can Japanese sovereign debt continue to increase without a crisis?) that predicts the turning point will happen within a decade at the time of his writing. We are approaching that turning point. His main argument is that the saving rate will finally go below zero due to the aging population. His prediction is right on, but the schedule has been moved up by the Covid response. Below is his calculation of the shift of Japan’s saving rate.

Such forces are unstoppable. We are seeing the beginning of a long decline of the Japanese yen.

Back to homepage.